GLENN: Today is a pretty important day in the court system. Today is the day that Jack Phillips goes to the Supreme Court. He is the owner of Masterpiece Cake Shop. And he refused to custom design a cake to help celebrate a gay wedding. And as a Christian, he says, I can't advance the message of gay weddings and -- and gay unions, because it's wrong, according to my religious belief. But he said, I'll sell you cupcakes. I'll sell you cakes. I'll sell you anything.

I just can't do the wedding cake. So he has no problem serving gay people. In fact, going another step, he has refused to make cakes for several people that weren't gay. Because he said, I don't agree with the message that you want to put on the cake.

I'm sorry. You want a topless woman with big bazoombas made out of icing, I don't do that. I won't do that. Okay?

So he has a long --

STU: Very strong anti-bazoomba stance.

GLENN: Yeah, very strong.

STU: I hope that's supported by the Constitution. I don't know that it is. I don't know that it is.

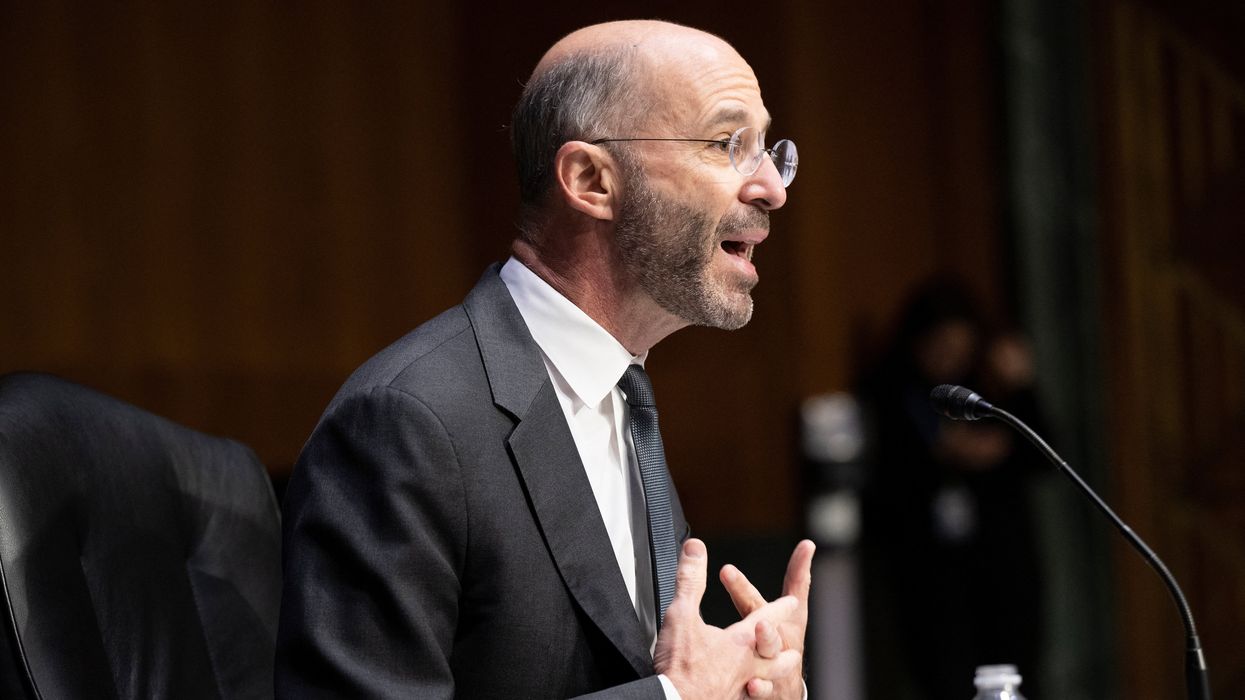

GLENN: But we have somebody on the phone that might know. David French. David, I won't start with the bazoomba clause in the Constitution.

But you wrote a great article. And you said that you're going crazy by the way this is being misrepresented. And Jennifer Finney Boylan is really the head of the snake on this one, from the New York Times.

DAVID: Yeah. It's a remarkable -- it's the most misrepresented Supreme Court case I've ever encountered, and here's how it's being misrepresented: Essentially what people are saying is that this cake designer's decision not to design a cake that advances a point of view that he objects to, is the same as segregated lunch counters. It's the same as refusing medical treatment to LGBT people. I mean, the parade of horribles that you're -- that you see spun out from this case is absolutely unbelievable.

GLENN: Explain.

DAVID: You hit the nail on the head.

GLENN: Explain to me why this isn't the lunch counter of the 1950s.

DAVID: It's very easy. He doesn't discriminate on the basis of identity. What he does is he decides not to advance certain messages that he agrees with. So if you're black, white, gay, straight, male, female, and walk into his bakery, you're going to be served. It is -- you're going to be served, regardless of your identity. Regardless of your membership and protected class. If you ask him to use his artistic talent to design a cake or any other thing that sends a message that he disagrees with, like in some of these cases it was like a Halloween message, then he's not going to do that.

And this is just common sense. This is normal stuff.

GLENN: Wait. Wait. Is it because the witches had big bazoombas? Is that what --

DAVID: Well, I've not explored that one.

GLENN: Okay. All right. Well, you should look into it. I know you're a serious thinker.

She goes on -- the New York Times says this -- and you just used this word, his artistic ability.

She wrote in the New York Times: Mr. Philips certainly makes nice-looking cakes, but I'm not sure I'd call them artistic expressions. At least not the same sense as say, Joyce's Ulysses. That argument demands that the court get into the business of defining art itself. A door the justices open at their own peril.

Is a well-manicured lawn a form of art by this definition? How about lean corn beef sandwiches? Would they not be art if the court rules to protect icing and butter cream?

DAVID: You know, that is so unbelievably absurd.

Here's what she's intentionally avoiding: The actual cake that this -- the gay couple settled on to celebrate their wedding, was a rainbow cake.

Now, are you going to tell me that that doesn't send a very clear message, that a well-manicured lawn doesn't send or a corn beef sandwich doesn't send -- she's acting as if the court has to decide the very definition of art itself, when all the court has to decide is, in this case, was he being asked to engage in artistic expression?

And this goes to something George Will sadly, mistakenly wrote, just the other day. He said -- he made much the same point, that this isn't art. It's primarily food. Are you going to tell me that a wedding cake is primarily food? Is that why people spend thousands of dollars sometimes to make sure that it's just a --

GLENN: I have to tell you something, my father was a baker. But he was -- he made wedding cakes. And he spent Fridays and Saturdays making wedding cakes. And they were -- they were pieces of art. And they took him forever. And it took him years and years and years of study and practice, to be able to practice that art.

And people would come from all over to get his wedding cakes. There is a difference. Otherwise, you just get a wedding cake at a Costco.

DAVID: Right. I mean, all you have to do to know it's art. It's like do a Google image search for beautiful a wedding cake. And you'll see amazing things.

You feel like people are being intentionally obtuse here. Everybody knows when one of the centerpieces of an entire wedding reception is the cake. It is one of the most talked about elements of the entire -- of the entire reception.

And, yeah, nobody wants it to taste badly. But they're talking about it because of the way it looks. Because of the way it expresses a view of the ceremony. The way it expresses the personality of the couple. All of that is undeniably artistic. And so, again, this is the most misrepresented case I've seen. They misrepresent the nature of what Jack Phillips did. And they misrepresent the nature of his work.

GLENN: So is this about art? Or is this about advancing a message?

DAVID: Well, it's -- well, in this case, it's -- it's both. It's about using your artistic ability to advance a message. And whether or not the state can force you as an artist to use your artistic ability to specifically advance a message. And that one woo run counter to generations of First Amendment case law. Generations that say, you cannot be compelled to advance a message that you disagree with.

GLENN: So most Americans -- as you point out, most Americans, if a white customer came in and said, I want a Confederate flag Klan cake. If that was an African-American baker, we would all say, he doesn't have to make that, man. He doesn't have to make that.

DAVID: Right.

GLENN: We would all understand that. And it would be fine. Now, if that baker said, I'm not serving any white people, and I'm not serving you anything, we still would understand, I'm not -- I'm not going to serve you because you're a Klan member. We'd still even understand it. But we would say it was wrong.

This is -- this is -- this is the -- you can't compare these two.

DAVID: Yeah. Even when the specific art doesn't send a very specific message -- now, think of -- remember when Melania and Ivanka Trump were getting ready for the inaugural ball, and all these designers said, I don't want to lend my artistic ability to design dresses for Melania and Ivanka.

Well, that was their right. They don't have to use their artistic talents to support a political family they disagree with, even though Melania and Ivanka are women and women are a protected class in public accommodation statue.

So this -- time and again, you can come up with these counterfactuals. And time and again, people on the left go, oh, well, that's different. Oh, that's different. Well, how is it different? And then they'll go, segregated lunch counters. Jim Crow.

GLENN: They'll say on her, she doesn't -- she wasn't born that way. She wasn't born that way.

DAVID: Well, she was born a woman. She was born a woman. And women disproportionately wear dresses. Or a person who wants a Confederate flag cake is disproportionately white. It's the same logic that they're using to try to claim their sexual orientation discrimination here. And they say, well, it's disproportionately, gay people would want a same-sex wedding cake. So, therefore, it's discrimination on the basis of status, which is false.

GLENN: So should -- I mean, just to make this point, should Melania or someone sue those -- I guess she would be the only one with standing, sue those people to make the point that, no, you don't have to make a dress for me.

If you don't want to, you're an artist. You don't have to make that dress for me.

DAVID: Well, you know, I do think if this decision turns out against Jack Phillips, people will start to do that. You will start to see these kinds of lawsuits popping up around the country, where say, for example, conservatives will then try to force progressives to advance their point of view. And then, you know, we're going to get into this mess, where we've seen this happen before, and what ends up happening -- when it's a particularly important sexual revolution issue to the court. Often, they'll carve out these distortions in the First Amendment. They did one for a long time. It became known as the abortion distortion, where if you were protesting abortion, magically, you would end up with fewer free speech rights than virtually anybody else.

What we're seeing in the clash between sexual liberty and free speech is all too often courts are carving out specific exceptions and specific special rules to help advance sexual liberty at the expense of First Amendment freedoms.

STU: Talking to David French.

David, I'm fascinated by this use of kind of a classic left-wing thing to say, which is that the courts can't define art. They've been saying that forever. But it's always used the other way, when something that might not be art -- it's always used to include everything is art. And in this one case, they can't find any art, in a beautiful wedding cake --

GLENN: A mason jar with piss and a crucifix is art, but this cake is not.

STU: But this cake is not. Isn't that a complete reverse of the way they usually use that argument?

DAVID: Oh, absolutely. For generations, there have been progressive lawyers arguing to expand the definition of protected speech under -- in the First Amendment. And many times, during so rightfully. Many times you doing so in ways that advance our liberty. But now all of a sudden, this thing that is obviously to any person, any objective reasonable observer is an artistic expression, suddenly it's primarily food.

GLENN: Well, it's primarily piss. So let me -- let me just ask you this last question. We have to cut you loose. The -- the court is hearing this case today.

The swing vote is Kennedy. Kennedy has already ruled in a way that looks like you should rule in favor of the baker.

What do you think is going to happen?

DAVID: Well, you know, if Kennedy holds to some of the language he wrote in the Obergefell decision, then I think Jack Phillips will win. I mean, in the Obergefell decision, Kennedy acknowledged that there are deep differences, religious differences, in particular, about the definition of marriage, and that the Obergefell decision was not designed to force anyone to profess agreement with a definition of a marriage that differs from the courts, that differs from the Obergefell opinion.

And in that circumstance, if Kennedy holds to that logic and holds to that reasoning and also holds to his own history of First Amendment jurisprudence, then Jack Phillips should win. But we'll -- of course, we'll see.

GLENN: Yeah. It could happen -- aliens could come down and just hold a conference on the steps of the Supreme Court, and it wouldn't surprise me at this point.

David French, thank you so much.

DAVID: Thanks for having me.

GLENN: David French, senior fellow and writer at the National Review.

STU: We'll tweet out his article. You can go to Glenn Beck or @worldofStu to get it.