Author Jon Ronson joined Glenn to discuss the affects of being shamed on social media. His book So You've Been Publicly Shamed tells personal stories about the terrifying phenomenon of social media shaming. One story details how a poorly crafted and misinterpreted tweet destroyed the life of a woman named Justine Sacco.

"We tried her, convicted her and sentenced her to a year in purgatory, not getting another job, while she was asleep on the plane and had no idea there was even a trial," Ronson explained.

RELATED: What Can You Learn From a Drunk, Sexting College Student? Mercy.

Following Justine's infamous tweet, the Twittersphere exploded with angry, hateful reactions, making her the number one trending topic within hours. And people thought it was hilarious.

"The number of tweets that were like, This is the best thing that's ever happened to my Friday night . . . #HasJustineLandedYet may be the best thing to happen to my Friday night . . . people thought it was so funny that she was unaware of her destruction," Ronson explained.

Listen to the full interview below or watch the clips for answers to these questions:

• What did Justine Sacco tweet before her trip to Africa?

• How is social media shaming related to fake news?

• How long did it take Justine Sacco to rebuild her life?

• Where did Glenn's family get publicly shamed?

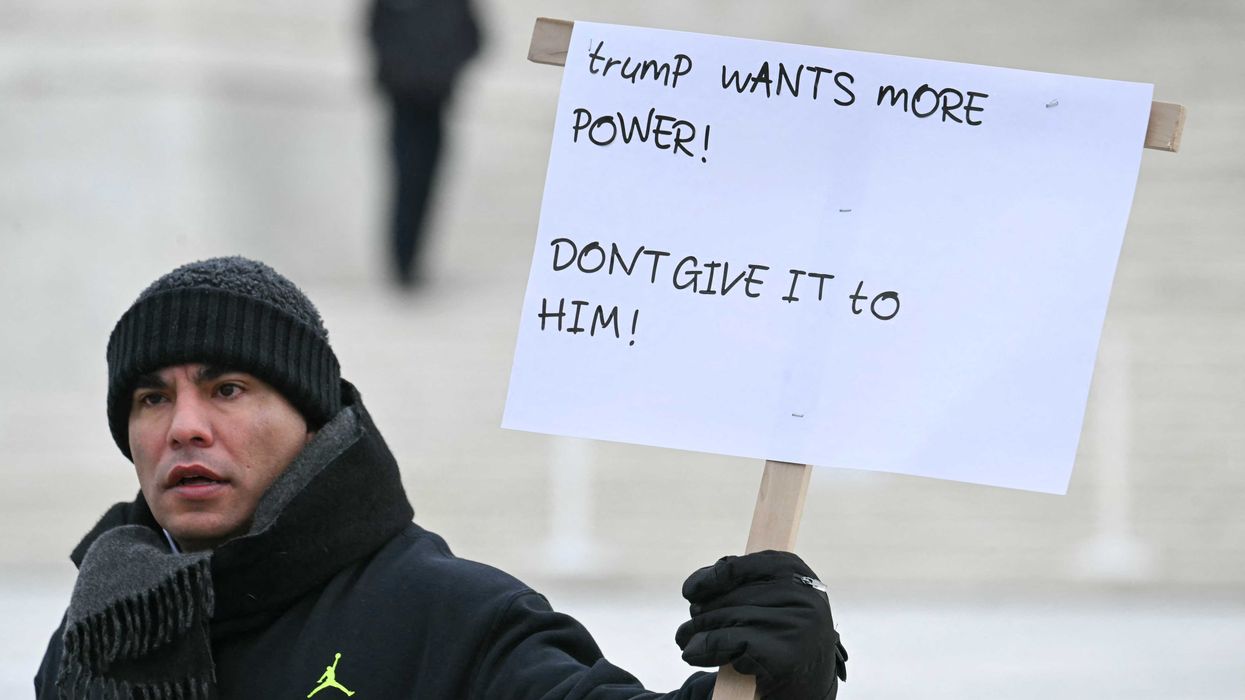

• Is social media shaming a human or political problem?

• How did Adria shame Hank on social media?

• How was Adria shamed in return?

• How is social media shaming like a modern-day witch hunt?

Below is a rush transcript of this segment, it might contain errors:

GLENN: We had a really fascinating discussion today that is focused on the internet and the role that it has played with fake news. I want to take it to public shaming. The way we crucify each other on the internet. And then we move on with our life. We say horrible things about each other, or if it's worse, you have said something, and then it's been taken and all of a sudden, you're the number one trending topic in the world. You're like, "What the -- and your life changes, but everybody moves on after we've wrecked your life. So You've Been Publicly Shamed is a name of a book by Jon Ronson. And he has talked to some of the most famous criminals of Twitter. I mean, people who have said horrible things, where we all had to stop our life and comment on them. And then we moved on.

What happened to them? We start there, right now.

(music)

GLENN: All right. I -- I want to start with the story of Justine Sacco. Ever heard of her? Do you know the name Justine Sacco? Anybody? Anybody? Stu does. Stu does.

JEFFY: Yeah. Just because we talked about it a little bit.

GLENN: Yeah. So you remember. But you would not know that name if you were the average person.

STU: Right.

GLENN: Yet you most likely know the story. We're going to start there with Jon Ronson, author of the book So You've Been Publicly Shamed.

Hello, Jon, how are you, sir?

JON: Hey, Glenn, I'm well. How are you?

GLENN: I'm really good.

I -- we were having this conversation the other day about a month ago internally, and we were like, "What happens with these people?" We've just moved on with our life, but their life is just a wreck. And Stu is a fan of yours and read this book. And he said, "Oh, you've got to read this book." So we wanted to bring you on and tell some of the stories because they are truly fascinating.

JON: They are. And by the way, I'm glad you equated it in a way to fake news. Because I think the two things are kind of corrected.

GLENN: I do too.

JON: Yeah. In a story like Justine Sacco the world --

GLENN: Wait. Wait. Wait. Before we get there. Explain how you think they're connected.

JON: Well, because when something like the just teen Sacco incident happens, and there's many incidents like that, the world gets to know a tiny liver of information about a person. And then they decide to draw huge amounts of inferences. A person is defined in that totality by a single tweet that they wrote. And then all hell breaks loose.

So it's kind of like fake news. You take a little sliver of a fact that means nothing, and you create an entire narrative out of it.

GLENN: Isn't it also a lot like celebrity news? I mean, the paparazzi, they take one picture. They take one salacious piece, and your whole life is destroyed.

JON: Yeah, I remember someone saying to me that one of the ironies is that Twitter claims to hate tabloids and tabloid television.

GLENN: Yeah. Uh-huh.

JON: Yeah. That's exactly how we behave every day.

GLENN: It is. It is.

Okay. So Justine --

JON: Yeah. This is a story of hypocrisies, I think.

GLENN: So Justine, she gets onto a plane, and she's going to South Africa.

JON: Yeah.

GLENN: And before she gets on the plane, she tweets.

JON: Well, she had been tweeting little stupid jokes all day. So when she went from New York to London, she tweeted something about a German passenger with BO. I mean, she was not great on Twitter. She was kind of acerbic and not hugely likable. But she had 170 Twitter followers and was basically -- basically a bad comedian tweeting into an empty room.

So she gets to Heathrow, and she writes the tweet that then went around the world. And the tweet was, "Going to Africa. Hope I don't get AIDS. Just kidding. I'm white."

PAT: Hmm.

JON: I mean, not good.

(laughter)

GLENN: You think?

JON: However -- however, when I meet Justine Sacco a couple of weeks later -- I'm to this day the only journalist who's ever interviewed her. And I met her in a bar. And I asked her to explain the joke.

And she said, "Living in America puts us in a bit of a bubble when it comes to what is going on in the Third World. I was making fun of that bubble." So when you look at it in that perspective, it's not that bad a joke.

STU: And I think it's kind of obvious from the joke.

JEFFY: Yeah.

STU: People are acting as if she thought white people couldn't get AIDS, which is obviously completely absurd.

It's obvious she was commenting on this disconnect between America and what goes on around the world.

GLENN: And, you know, you say it's a bad joke. And it's tasteless joke. And not funny because she's not a comedian. But isn't that -- jokes are kind of like art. It's all, you know, subjective to some regard. And everybody does that. Everybody jokes. It's not like you have to have a license to make a joke.

JON: Sure.

I mean, I suppose what you could say about that joke is that it's a kind of poorly executed version of a kind of (inaudible) little joke.

So, for instance, it's exactly the kind of jokes that's made in South Park all the time. It's the kind of joke that Randy Newman, who I love, has based a career on. You do a kind of exaggerated version of your own privilege and mock it. So it's actually a left-wing joke. But she never got a chance to explain that to anybody because of what happened next.

GLENN: Okay. So she gets on to the plane. They seal the door. They say, "Turn off your phones and your devices, and we'll turn them back on once you get to South Africa."

JON: Right.

GLENN: Anybody who has flown over just the continent of Africa knows, "That's a never-ending trip."

JON: Right. It was about 11 hours of blissful ignorance she slept.

There was no Wi-Fi/internet on the plane. So -- and then she woke up in Cape Town, as the plane was taxiing on the runway. She turned on her phone. And immediately, a text came up from a friend -- from somebody she hadn't spoken to in 20 years that said, "I am so sorry to see what's happening to you right now."

And then she looked at it kind of baffled. Had no idea what was going on. And then another text from her best friend that said, "You need to call me right now. You are the worldwide number one trending topic on Twitter."

GLENN: Imagine how your heart would sink.

JON: Yeah.

GLENN: Oh, my gosh. What is happening? So what was happening was ugly.

JON: Right. Yeah, I mean, horrendous.

I should say that I don't -- some people see this as a kind of politically biased story mainly because in this particular story, it was the left going after her more than I would say than the right. Although, kind of everybody went after her. But these stories happen all the time. Sometimes it's the right against the left. Sometimes it's the left against the right.

It's the kind of horrificness of the story I think that matters as opposed to which side of the political spectrum you are.

GLENN: And she was actually left --

STU: It was left going after left.

GLENN: After left. Right? Yeah.

JON: Yeah, exactly.

Well, so the first thing that happened was one of her 170 Twitter followers sent the tweet to a journalist at Gawker called Sam Biddle.

GLENN: Oh, my gosh.

JON: I know. And so he delightedly retweeted it to his 15,000 followers saying -- I spoke to Sam Biddle not long afterwards. And I said, "How did that feel, to have started the onslaught against Justine?" And he said, "It felt delicious." And then he said, "But I'm sure she's okay now." But she wasn't okay.

GLENN: Unbelievable. Unbelievable.

JON: Yeah. "I'm sure she's okay now." You know, we love to play psychological tricks on ourself to not feel bad about the bad things that we do.

GLENN: So -- so when you met with her, how long after this absolute firestorm. She lost her job. Her life was destroyed. In the book, you say, "Well, it wasn't necessarily the perfect job for you." And she's like, "Yeah, I think it was my ultimate dream job," that she lost.

JON: Yeah. It was -- she -- and the thing is, it was everybody. Her shaming was a shaming that the whole world would get behind. So philanthropists started shaming her and tweeting things like in the light of this disgusting joke, I am donating aid to Africa. And then trolls started going after her saying, "Somebody HIV positive should rape her, and then we'll find out if her skin color protects her from AIDS."

PAT: Oh, jeez.

GLENN: Oh, my gosh.

JON: Of course, nobody went after that person.

A hashtag started trending worldwide, #hasJustinelandedyet. And people were tweeting that I'm in this bar, and I really want to go home and go to bed. But I can't until Justine Sacco lands and she sees what happens when she turns on her phone.

GLENN: And she didn't even know. When she's walking in the airport -- I saw this in your book, a picture of her walking in the airport. And somebody takes a picture and tweets. Here, she's finally landed, and she's wearing sunglasses to hide her shame.

Did she even know at the time?

JON: Right.

At that point, she knew. I think she had found out. Because that was at baggage claim, and she found out as she was getting off the plane. So I think she had known for about 20 minutes. But I wouldn't say it was -- well, was it shame? I mean, it was certainly fear and distress and agony.

GLENN: Yeah. Yeah.

JON: And maybe some shame. She -- oh, you know, corporations got involved. Gogo, the internet -- you know, the flight internet people tweeted something like, "Next time you're getting on a plane, Justine Sacco, maybe you should choose a Gogo flight." So corporations got involved.

GLENN: Jeez.

JON: Of course, her employers essentially fired her over Twitter. Somebody linked to a flight tracker website so the whole world could watch as her plane got closer and closer to landing.

STU: The worst instincts of humanity.

GLENN: So I want to go -- because there's a couple of things in this story. We have two other stories I want to get to.

But there's some other things in this story about group madness and what you write about, a poorly worded joke, et cetera, et cetera. But I -- I want to know how long after did you talk to her? And have you talked to her since?

What has changed in her life?

JON: Okay. So the first time I talked to her was probably about two weeks later, when I met her in a bar. And she was just crushed. I mean, she couldn't stop crying.

GLENN: Two weeks later.

JON: She just couldn't believe this sort of -- that the whole world had gotten her wrong. She just couldn't -- she couldn't believe it. And then I spoke to her again a couple of weeks after that. She lost her job. And she continued to lose her job for about a year when she finally got a new job. And, of course, when Twitter found out that she had finally got a new job after a year, they tried to get her fired all over again.

JEFFY: What?

GLENN: Oh, my gosh.

JON: I know. Because, you know, when we watch Making a Murderer, whose side are we on? We're on the side of the kind-hearted defense attorney. But when we have the power, what do we turn into? Hanging churches.

GLENN: Really, we are witch hunters.

JON: Yes. But I don't want to go too far with my metaphors. But I remember at one point in the midst of this, I sort of yelled to my wife, "It's like the Year Zero. It's the Khmer Rouge." And my wife was like, "It's not like the Khmer Rouge."

(laughter)

GLENN: Yes. Yes.

PAT: A little context.

GLENN: But honestly, it is the same mentality of the witch hunt. We're just not burning them at the stake.

PAT: Exactly.

JON: Yes.

GLENN: But it is the same group insanity.

JON: Yeah. It really is. And it's done -- you know, in the old day social --

GLENN: For sport.

JON: -- psychologists would say, this is madness. This is literal madness that we lose our sense of sanity in the crowd. But I don't think that was what was happening. What was happening was people -- you know, within the echo chamber of Twitter, people wanted to -- it was like a sort of performance piety. People wanted to show the people who followed them on Twitter that they cared about people dying of AIDS in Africa. So to perform that kind of public compassion, anybody committed this profoundly uncompassionate act of tearing somebody apart while she was asleep on a plane.

GLENN: All right. Jon -- we'll be back with Jon Ronson. The name of the book is So You've Been Publicly Shamed. It is a fascinating look at the past. But also, the future. Because we are one tweet away, each of us, from this happening to us. And do you think you're not, you know, open for this. Well, she didn't think so either. Everybody -- she had 170 Twitter followers. Nobody was following her.

[break]

GLENN: So, Jon, we were talking during the break -- we're with Jon Ronson. So You've Been Publicly Shamed. We're talking about that woman that went over to Africa on the plane. She tweeted something. It was taken out of context. She was incommunicado for 11 hours. The world went crazy. We're looking for our tweet. We think that we tweeted a kind of --

STU: We talked about it on the show.

JEFFY: We talked about it on the show.

GLENN: Or we talked about it. A weak defense of her. Because we didn't know all the facts. But we were like, "This sounds like a joke."

STU: It's written that way. It looks like it's a joke mocking the separation.

GLENN: Right. So -- and we're looking up for the tweets because we believe we were also attacked. And this is the problem. This is why people don't say, "Hey, guys, let's be reasonable."

JON: Yeah.

GLENN: Because then, immediately, oh, of course, you're saying that. You're a hater too.

JON: Right. In fact, a really great British feminist writer called Helen Lewis that night tweeted, "I'm not sure Justine Sacco deserves what she's getting. Maybe her tweet wasn't intended to be racist." And straightaway, she got a whole bunch of tweets like, "Well, you're just a privileged bitch too."

JEFFY: Yep.

JON: So -- and so to her shame, she wrote about my book, and so I know this story. To her shame, she stayed silent and watched as Justine Sacco's life got torn apart.

GLENN: And she feels bad about that that now.

JON: Yeah, and feels bad about it.

GLENN: How does the Gawker guy feel?

JON: You know, actually in the summer -- he wrote another article about her when he discovered that she had got a new job. Wrote another article saying, you know, the lousy has-been's got a new job. So Justine, who I've stayed in touch with the whole time, emailed him and said, "Look, we've got to have a drink to sort this out."

So he met her for a drink and then wrote a bit of a mea culpa article afterwards. Yeah. So he did some mea culpa.

GLENN: Really quite amazing how we don't see people as people.

JON: Yeah. I'm -- you know, both sides do it. That story, in particular, from my book, became really famous. Because I wrote an excerpt for it for the New York Times, and it became really famous. And I think a few people misunderstood as a result, thought my book was an attack on the left. But that's not it at all. I mean, there's plenty stories in my book about the right doing exactly the same thing.

GLENN: Yeah. It's not a left or right thing. It's a human thing. It's like racism. Racism exists everywhere.

JON: It's a human thing. For me, it's a story about justice. Like, you know, what we did with Justine Sacco was, we tried her, convicted her, and sentenced her to a year in Purgatory, not getting another job, while she was asleep on the plane and had no idea there was even a trial. And not only was there no feelings of guilty about that, people thought it was hilarious. The number of tweets that were like, "This is the best thing that's ever happened to my Friday night." #JustineSaccolandedyet may be the best thing to happen to my Friday night. People thought it was so funny that she was unaware of her destruction.

GLENN: Oh, my gosh. We have -- we have two more stories of destruction. And are we engaging in this? Next.

[break]

GLENN: Welcome back. Welcome back to the program. Jon Ronson is with us. He is the author of So You've Been Publicly Shamed.

We've been talking about fake news. And I'm particularly interested in the ability of the average person to destroy and to be destroyed because now we're all publishers. We are all able to publish something to the entire world. And the entire world gets to judge a book by your one tweet or your one Facebook mention. And that's it.

I mean, we are judging a book by the cover. And it's a frightening thing when you come to think about it and you see the people who have been destroyed.

Jon, should we go to Hank?

JON: Sure.

GLENN: How do you say her name?

JON: Adria.

GLENN: Adria.

JON: Yeah, this is a particularly I think kind of upsetting and difficult story.

So it begins at a tech conference in Santa Clara. Hank is sitting, chatting to a friend, making stupid kind of Beavis and Butt-Head type jokes. Something is happening on the stage about dongles. And Hank whispers to his friend something about dongles, like some kind of stupid joke, but like whisper.

As he told me afterwards, it wasn't even conversation-level volume. So the woman sitting in front turns and takes a photograph. And Hank assumes that she's taking a photograph at the crowd. So he tries to not get into her shot.

But then a few minutes later, Hank and his friend are called out of the conference and told that -- there'd been -- a complaint about sexual language.

So they apologized and then -- because they're kind of nerdy guys, they left the conference. You know, they didn't like conflict. So they left the conference.

On their way to the airport, they saw what happened there. Like what happened.

And the nightmare scenario is that the woman in front had complained via a public tweet on Twitter. And that is exactly what happened. She'd -- she'd sent -- she'd tweeted the photograph of the two men with the comment, something like, "Not cool. Jokes about big dongles, right behind me." And so two days later, Hank was called into his boss' office and fired.

So that night, Hank went on to Hacker News, a message board saying what had happened. Saying, you know, I was fired. You know, I -- I shouldn't have said what I said, but the woman in front just smiled and --

GLENN: It's a stupid -- it's not even her business. It wasn't directed to her. I mean, why does anybody care?

JON: Right. Well -- before we go on to that. Can I tell you what happened next?

GLENN: Yeah.

JON: Because what happened next was really important too.

GLENN: Yes.

JON: So Hank was fired, and then 4chan and the other groups all decided to get Adria. Now -- and so she was then subjected to months and months of photographs of beheaded women with tape over their mouths and death threats.

GLENN: Oh, my gosh.

JON: And rape threats. And she lost her job too. So it was just carnage. I mean, everyone was just like babies crawling towards guns.

(laughter)

I think what it shows is that we are -- social media is such a kind of primitive thing. And all we can think to do is lurch towards outrage and lurch towards shaming. So a woman shames a man in an inappropriate way. What did the men then do? Shame her back in an even more inappropriate way.

I think -- these are the -- these are the stories that maybe in years to come will form chapters and books about how Donald Trump ended up being our president.

GLENN: I think -- I think in many ways, you're right.

JON: Yeah.

GLENN: I will tell you this, this is probably about six years ago. And I would like to go back into the Twitter feeds and see what could be found now. But I remember as a family, we were in a park in New York. And, Ron (sic), you're from the UK, right?

JON: Right. Yes. Yes.

GLENN: Yeah, so I'm not sure if you know how unpopular I can be in the United States.

JON: I am. I am aware.

GLENN: You're aware. I've made international fame.

So I was in the -- the -- Bryant Park, when I was in New York. And people were mocking my family. And one woman spilled wine on my wife intentionally. And the reason why we know is because they started tweeting things about, Glenn Beck's family is here. And ha, ha, ha how funny it is. I accidentally, in quotation marks, spilled wine on his wife. People also think they're invisible while they're --

JON: Yeah.

GLENN: You know what I mean?

And maybe that's six years ago. But these people in this crowd didn't -- didn't think that we would also be reading what's being said.

JON: And if did you do anything about it?

GLENN: We left.

JON: Right.

GLENN: I just took my family -- we were surrounded. My children and my wife got up to go to the bathroom, and they were almost half a block away from me. And they were being chanted at, "We don't want your kind here." And it was -- it was just -- it was a mob scene. It was a mob scene.

JON: Right.

This is why -- I -- personally, I think kind of conciliatory centrism has become really unfashionable. And there should have been more of it the night Justine Sacco got destroyed. But, in fact, being a centrist was considered to be like a weakness. Like if anybody said, "Let's wait for her to land so we can hear what she has to say about that joke," people thought that was kind of pathetic weakness.

Like, why should we wait to hear what she has to say? We know what she means. That was a clue to her kind of secret inner evil. So as a result, I really admire anybody who is trying to move away from this kind of, you know, pollution of polarization. And I've noticed that that's what you've been doing lately, Glenn. And I really appreciate it. I think people on all sides need to do what you're trying to do.

GLENN: Well, I will tell you, Jon, that's one of the reasons why I wanted to have you on. Because the first thing is to make people aware of what's happened and to start to see people on Twitter as people.

JON: Yeah.

GLENN: Because I don't think we would do this -- well, I mean, I just told you a story in Bryant Park where it was in person. But for the average person --

JON: But you're Glenn Beck.

GLENN: Yeah, I'm Glenn Beck. So I'm not a person anymore.

JON: Right. And you're right. Everybody, Glenn, on Twitter has become -- everybody on Twitter has become like corporations that have to learn damage limitation, which is very stressful, given that Twitter was supposed to be kind of fun.

GLENN: Yeah.

JON: And Twitter was supposed to be like a fun way to connect with our fellow humans.

GLENN: Go ahead.

STU: Jon, this is an interesting point on this. Because the two examples we've talked about so far, both Justine Sacco and the guy with a dongle joke, I think to a conservative audience, you say, this is ridiculous. You know, you make a kind of an off-color joke, and maybe it's not right, but you get beat up and you get fired for it.

I like that the example you have of Lindsey Stone -- because to our audience, I think it's more challenging. But all the same principles apply here.

JON: Right. Yes. Absolutely.

So Lindsey Stone, you couldn't meet a nicer person. I mean, on many levels, Lindsey is even more sympathetic -- I mean, I think most people are sympathetic.

But she works with adults with learning difficulties and was great at her job. Took them on a trip to Washington, DC. Sort of went to the mint and the Holocaust Museum. And then they went to Arlington. And Lindsey and her friend have this little douchey joke that they would share amongst their Facebook friends. And the joke was to stand in front of the sign and do the opposite. So they would smoke in front of a no smoking sign or loiter in front of a no loitering sign.

JEFFY: It's funny.

JON: It was just like a little private joke.

Anyway, at Arlington, they see a sign that says, "Keep off the grass," and they thought, "Should we?" And they thought, "No, we don't want to get in trouble." Then they saw another sign that said, "Silence and respect." And so, as Lindsey told me later, "Inspiration struck."

(laughter)

They were pretending to shout and flip the bird. And so she puts it out on Facebook. And then a friend of hers who was in the military said, "I think that's kind of disrespectful. You should take it down." And Lindsey went, "Oh, don't be ridiculous. It's just us being us. You know, it doesn't mean anything." And then they forgot all about it.

And then a month later, suddenly, it just went super viral. Some pro military website had picked up on it, and she got everything that just even got. Death threats. Rape threats. And because it was from the right, it was things like -- you know, when it was Justine, it was like, "Typical privileged white woman," when it was Lindsey, it was "Typical feminist." So it's exactly the same. Exactly the same demonization happening, just from a different spectrum.

And it went on and on and on. And Lindsey was completely ill-equipped to deal with it. So she went from being this happy-go-lucky young woman who went to karaoke to somebody who stayed home for a year and a half, having suicidal thoughts, depression, anxiety, insomnia. Of course, she lost her job too. And, you know, by the time -- go on, sorry.

GLENN: No, no, no. Go ahead. By the time...

JON: By the time, I met her -- again, she was just crushed. I mean, we always end these stories by thinking, "Well, I'm sure they're fine now." But they're not -- I mean, people kill themselves. Everybody I spoke to will have complemented suicide. But some people do kill themselves.

Frequently, people kill themselves because of social media shamings. And there's no outrage about that because we don't want to feel bad about the bad things that we won't be.

STU: But there doesn't seem to be a line in our society anymore of -- like, if Barack Obama went into Arlington and flipped them off and started fake screaming in front of the sign, I think there would be a righteous outrage over that act. But some person we don't know -- we don't know anything about them --

GLENN: We all want to be outraged.

STU: Yeah. Why? I don't want to live like that. Why does everyone want to live like that? I don't get it.

GLENN: I don't either.

JON: I think it's in part because social media, in its earliest form, it was kind of a beautiful egalitarian thing, where suddenly everybody had a voice. So voiceless people had a voice. And by voiceless, I mean, you know, people from marginalized communities. And I also mean people who were so socially awkward in real life.

GLENN: Oh, yeah.

JON: That when you met them at a party, they'd just be standing in the corner of the room. But suddenly they -- on social media, they were funny and eloquent.

And this was like powerful. But -- and then we thought, "Wow, we can do things. We can right wrongs." So we would get people who kind of deserved it.

I mean, I can think of lots of things in the early days of social media when a corporation had done something really bad, and social media put pressure on them and they changed their policy.

But then, you know, I think what happened was that a day without a shaming felt like a day sort of picking fingernails and treading water. It's like we fell in love with getting people so much, that we lowered our standards and started getting anyone.

GLENN: So let me ask you this -- have you watched Westworld, the TV show on HBO?

JON: Yes, I have. I watched the last episode last night.

GLENN: Okay. It was great, wasn't it?

JON: Great.

GLENN: One of the best endings -- but let's stay on track. Sorry. Riddled with ADD.

STU: Come back for another hour-long interview on Westworld.

JON: Right.

GLENN: Yeah. So, Jon, the question in the park is, does the park make you into something, or does it reveal who you are?

JON: I think in terms of social media, part of the -- part of it is this is lying dormant within all of us. But it's also partly because of the technology itself.

Social media is created by engineers. You know, it's engineered in Silicon Valley. And what do engineers love? They love stability. They love everything going along, nicely. And that's why I think Twitter has evolved into a kind of echo chamber, where we surround ourselves with people who feel the same we do and we approve each other. And that's like a good feeling.

And then -- and it's such a powerful feeling, that when somebody gets in the way who is not like us, like Lindsey Stone or Justine Sacco, we're like a machine furiously ejecting a destabilizing fragment. So I think the machine contributes to -- to the problem.

GLENN: Jon, I would love to have you in and spend more time with you in person. Because I just think you're a fascinating guy. And this is -- this is something that I think historians will be reporting on. This is the beginning of a massive cultural change globally and what we do and how we, each of us, act as leaders in our own home, in our own circle of influence, and how we either hang ourself or don't hang ourselves as individuals is important. And I'm glad you're watching this, Jon. Thank you so much.

JON: Thank you, Glenn. I really appreciate it.

GLENN: You bet. Jon Ronson. The name of the book is So You've Been Publicly Shamed. It is a fascinating look of stories that you have heard.

STU: Yeah.

GLENN: But you've never heard it from their side. You've never seen what happened afterwards. Isn't it amazing? He's the only -- only person in the media to reach out to her, to this day.

STU: Well, at least successfully.

JEFFY: Right.

STU: Since he wrote about it, I'm sure people have been interested.

GLENN: I'm sure people also -- she's not taking very many that she doesn't know. Yeah.

STU: No. She wants out of this.

Featured Image: Be More Human: Mindshare meets Jon Ronson during Advertising Week Europe 2016 at Picturehouse Central on April 18, 2016 in London, England. (Photo by Jeff Spicer/Getty Images for Advertising Week Europe)

ALEX WROBLEWSKI / Contributor | Getty Images

ALEX WROBLEWSKI / Contributor | Getty Images

JIM WATSON / Contributor | Getty Images

JIM WATSON / Contributor | Getty Images Joe Raedle / Staff | Getty Images

Joe Raedle / Staff | Getty Images AASHISH KIPHAYET / Contributor | Getty Images

AASHISH KIPHAYET / Contributor | Getty Images